For a country with a strong uranium mining industry, a legacy of nuclear weapons testing and globally unique geology, Australia knows surprisingly little about some of the radioactive materials lingering in its environment. Unlike the northern hemisphere, where decades of nuclear activity and sustained investment have produced large datasets, knowledge of Australia’s radiological picture is more limited.

Filling that data gap is one of the projects underway at the ARC Industrial Transformation Training Centre for Radiation Innovation (RadInnovate). For Research Fellow Madison Williams-Hoffman, who joined the Centre in mid-2025, it’s work that’s overdue and incredibly important.

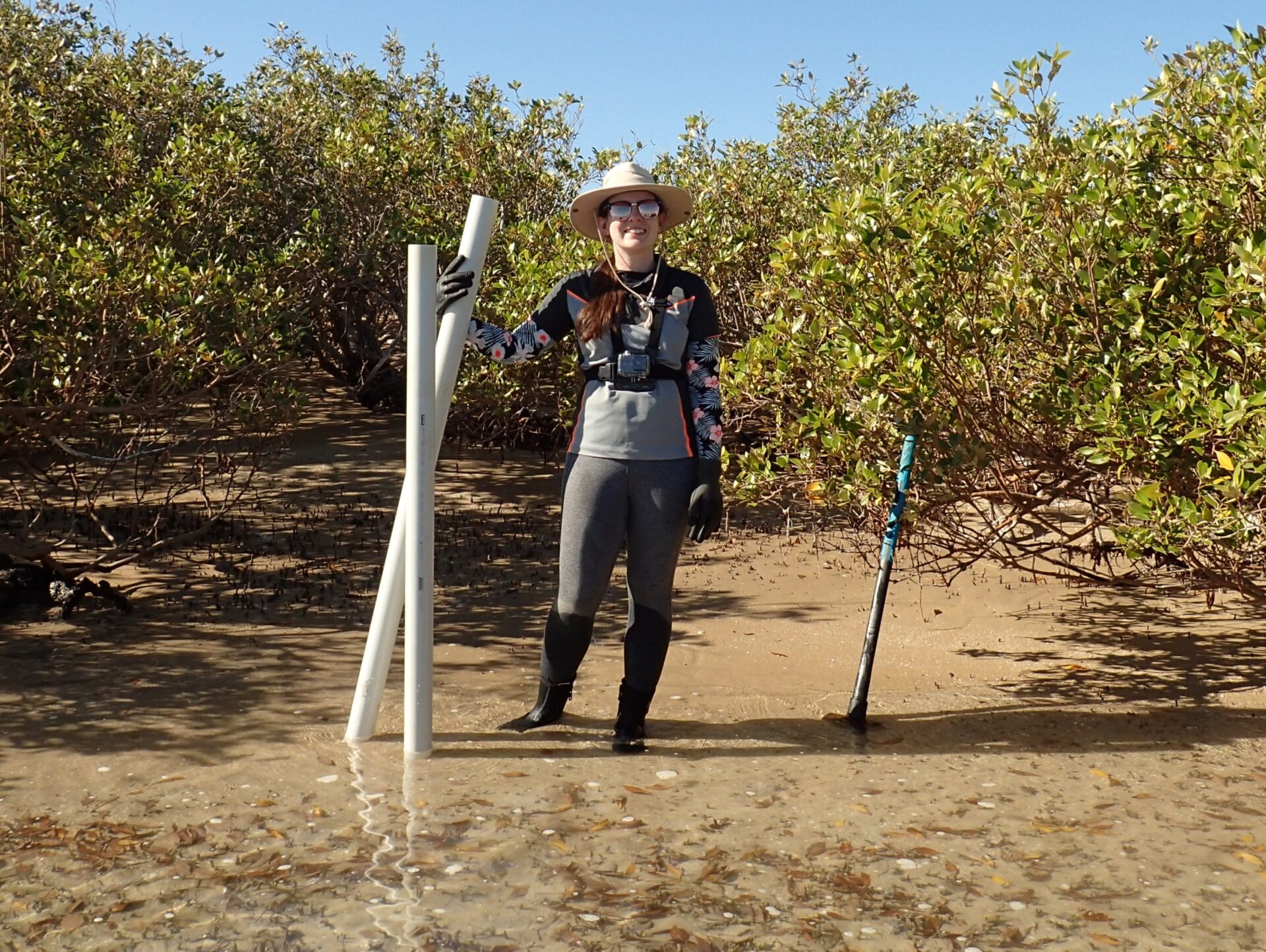

Her research background centres on tracking anthropogenic radionuclides — isotopes left behind by weapons testing — in the Australian marine environment.

“In Australia, we don’t have much data about how anthropogenic radionuclides behave in our marine and terrestrial environments,” she says.

“Where are they? What are they doing? How have they persisted for the past 70 years since nuclear weapons testing ended in Australia?”

The Heavy Ion Accelerator Facility (HIAF) at the Australian National University (ANU) pioneered using accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) to measure such radionuclides at the extraordinarily low concentrations that persist in the environment today.

“Because these radionuclides exist at such low levels, they’re extremely hard to measure,” she says. “AMS allows us not only to measure them, but to identify their atomic ratios to compare one isotope to another. That acts like a fingerprint that tells us where they came from.”

At RadInnovate, in partnership with Queensland Health, Madison is applying her expertise to a broader challenge: building the first comprehensive environmental baseline dataset for several understudied radionuclides in Australian environments. These include protactinium-231 and actinium-227, decay products of uranium-235.

“People have assumed these radionuclides didn’t have much impact because they’re present at far lower activity levels than decay products from the more abundant uranium-238,” she says. “But assumptions aren’t evidence. We can’t understand risk or movement in our environment without data, especially at sites with elevated uranium levels, like mining areas.”

Collecting that data requires the specialised AMS capabilities at HIAF. Its technical staff collaborate with users to design and build bespoke instruments and methods, making it uniquely suited to tackling questions no one has answered before.

“It blows my mind that if you need a new tool, the team at HIAF can just build it,” Madison says. “That level of flexibility is rare anywhere in the world.”

Once data is collected, the next steps include dose modelling: determining whether identified concentrations pose risks to people, wildlife or ecosystems, and how to act on those findings.

“There is a real lack of Australian-specific data about radionuclides in our environment,” Madison says. “At RadInnovate, we have a chance to fill that knowledge gap with real data that will help build better protections for people and our environment.”

There are also opportunities for PhD students at RadInnovate, including work on the baseline project. The Centre is seeking people interested in nuclear and radiation science who are curious and open to interdisciplinary research.

“These projects go beyond traditional discipline boundaries,” Madison says. “You might be a physicist one day and a fish biologist the next. And we can support students in developing the skills they need.”

Each project will be co-designed with industry partners like Queensland Health, BHP, ARPANSA and DSTG. More information is available on the RadInnovate website.