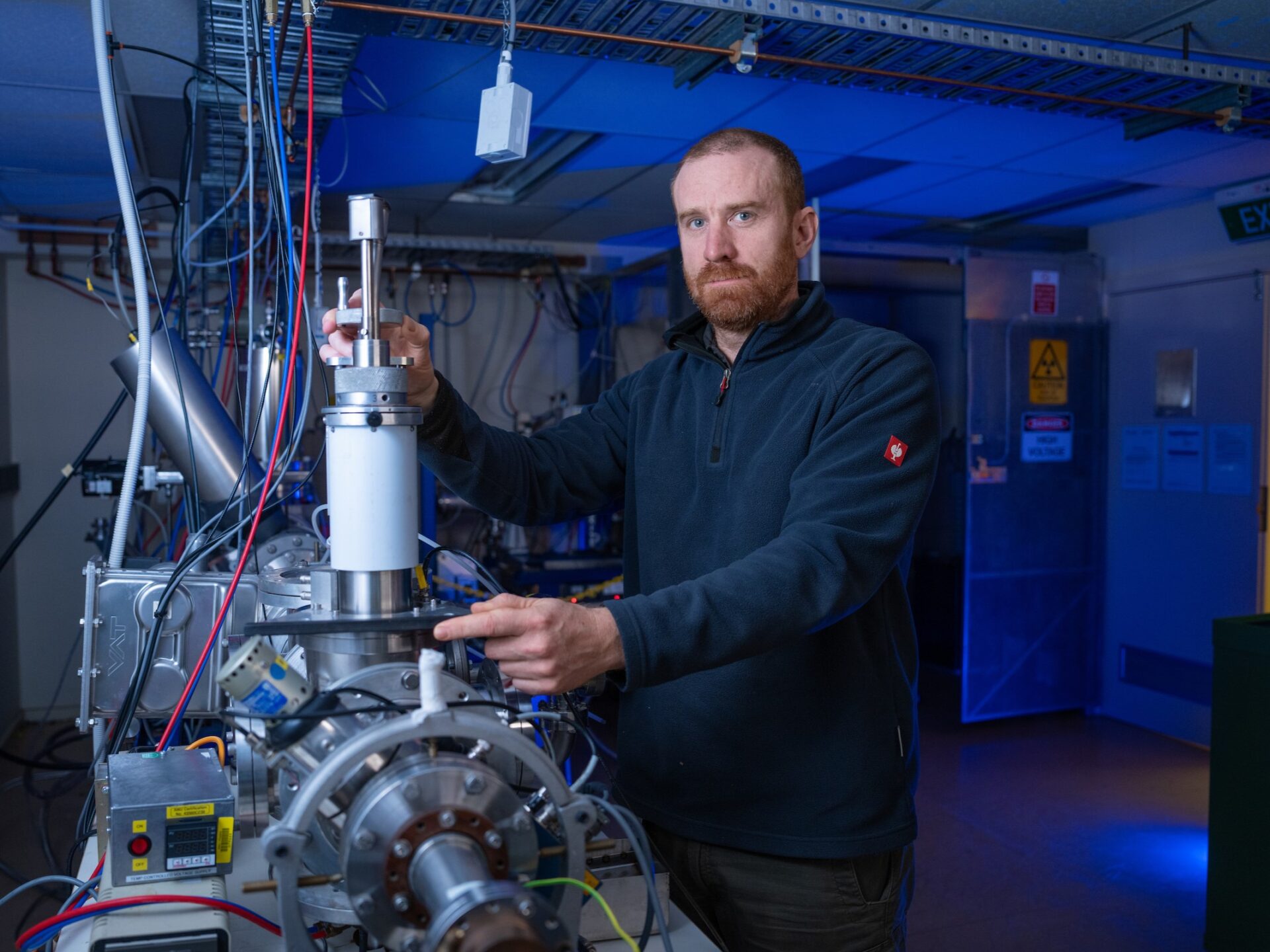

When Technical Officer Tom Kitchen was shown a scientific paper from the 1980s, he didn’t expect it would become the blueprint for an important upgrade at the ANU Ion Implantation Lab (iiLab), part of Heavy Ion Accelerators (HIA).

“Professor Rob Elliman [Director, iiLab] came to me with this paper and said, ‘Tom, we’d like to make something like this,’” he says. “My role was basically to try and turn something from a scientific paper into reality.”

The paper, written more than 40 years ago at Goethe University Frankfurt, outlined a design for a positive ion source, a watermelon-sized device that produces elemental ion beams that can’t be generated with the negative ion sources currently used at ANU.

Adding this positive ion source opens new possibilities for iiLab’s low-energy implanter, which fires a beam of ions into materials to change their physical, chemical and electrical properties. These capabilities underpin work in quantum technologies, semiconductors, advanced materials research and more.

A positive step forward

Negative ion sources work extremely well for many use cases, but not all. “You can’t turn every atom into a negative ion,” Tom explains.

Workarounds exist—for example, breaking up molecules in the high-energy implanter to obtain the ions researchers need—but they don’t suit low-energy applications and can introduce contamination.

This matters for elements like erbium, a key optical dopant for quantum communication, which can’t be implanted as a negative ion. Nitrogen, essential for creating NV centres in diamond for quantum sensing and computing, won’t run as a negative ion either. A positive ion source allows researchers to implant both as pure elemental ions.

It also enables implantation of rare earth elements and inert gases like helium, argon and xenon. “It lets us cover pretty much every species in the periodic table as elemental ions,” Rob says. “Once this is complete, we’ll be able to offer a much wider range of species and energies.”

The new source directly supports research and development across quantum computing, optics, materials science and solar cells. “Our facilities are unique in Australia, and when users have time-critical projects, our staff can respond quickly to meet their needs,” Rob says.

Building from scratch

Tom has worked across ANU’s accelerator facilities for more than a decade, but recreating a 1980s design from scratch has been a first. “Scientific papers generally don’t include the technical details you need to build the thing,” he says.

Fortunately, Rob was able to contact colleagues at the lab where the source was originally developed, who generously provided drawings and extra information.

Tom translated the decades-old sketches into modern CAD drawings before fabrication began at the ANU Research School of Physics. “The Mechanical Workshop machined all the components, the Electronics Unit team have been involved, and I’ve done a lot of the welding and design work myself,” he says.

After sourcing the remaining components, including the power supply, construction of the device is now complete. The team is finalising the computer control system before testing and commissioning the new ion source, which they hope to have running by mid-2026.

“I’m sure that the original researchers would be delighted to learn that the ion source they dreamt up 40 years ago is being remade in Australia,” Tom says.

“It’s quite a challenge to bring a scientific paper to life. But it’s been fun.”

The positive ion source development project is funded by NCRIS. With thanks to Lothar Schmidt, Goethe University Frankfurt, for providing additional information to the scientific paper; Richard Koltermann, ANU Physics Mechanical Workshop; and Matthew Holding and Michael Blacksell, ANU Physics Electronics Unit.